09-14-21

Introduction

It has been nearly 60 years since, in the words of E.O. Wilson, “Silent Spring delivered a galvanic jolt to the public consciousness and …infused the environmental movement with new substance and meaning.” (“Afterword” to the 2002 edition of Silent Spring)

It has been nearly 60 years since, in the words of E.O. Wilson, “Silent Spring delivered a galvanic jolt to the public consciousness and …infused the environmental movement with new substance and meaning.” (“Afterword” to the 2002 edition of Silent Spring)

Rachel Carson’s courageous, ground-breaking book awakened Americans to ecological values as well as to the perils of the chemical pest control practices adopted after World War ll.

In 1962 Carson’s Silent Spring documented chemical pesticides’ adverse impacts on plants, bees, birds, beneficial insects, and aquatic organisms many of those that now we regard as precious sources of essential nature-based services. Carson also reported on the linkage of various chemical pesticides to human health problems including cancer, using information obtained from research with laboratory animals and reports by physicians.

Environmental legislation passed following Silent Spring’s publication included the 1973 Endangered Species Act (ESA). It was approved by a nearly unanimous vote in Congress and has been described as, ““In concept and effect…the most important piece of conservation legislation in the nation’s history.” (“Afterword” in 2002 edition of Silent Spring)

Why the 1973 Endangered Species Act Matters

Below we contemplate how Rachel Carson might view the current Endangered Species Act (ESA). We briefly consider ESA’s history and its relevance to the herbicide glyphosate and the insecticide chlorantraniliprole. Greater protections from pesticides’ hazards need to be enforced for species listed under the ESA as well as for non-listed species in precarious positions, especially our essential wildlife allies. We conclude with a list of citizens’ actions to better preserve biodiversity and nature’s services.

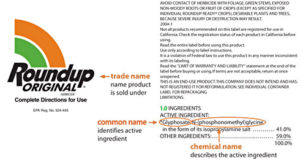

About Glyphosate

Carcinogenicity continues its association with chemical pesticides, most recently with glyphosate, a chemical herbicide developed since Carson’s day. On March 20, 2015 this widely used, potent, plant killing chemical was classified as “probably carcinogenic to humans…” and linked to non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. (The World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Monograph 112). (Footnote 1)

Carcinogenicity continues its association with chemical pesticides, most recently with glyphosate, a chemical herbicide developed since Carson’s day. On March 20, 2015 this widely used, potent, plant killing chemical was classified as “probably carcinogenic to humans…” and linked to non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. (The World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Monograph 112). (Footnote 1)

On May 27, 2021 a Judge’s announcement delivered a setback to the chemical giant Bayer (present owner of glyphosate, following its purchase of Monsanto). This American judge rejected the company’s plan to limit the cost of future claims that its widely-used, controversial product, Roundup causes cancer. (“Judge rejects Bayer’s Roundup proposal,” Reuters/Wash Post, 5-27-21) (Footnote 2)

Subsequently, Bayer confirmed that “they would end the sale of glyphosate-based herbicides for the U.S. residential lawn and garden market. There will be no change in the availability of the company’s glyphosate formulations in the U.S. professional and agricultural markets.” (7-29-21, Sustainable Pulse)

The November 2020 announcement from the US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) that “Glyphosate likely harms nearly all endangered species” presented another problem for glyphosate-containing products. This 2020 draft biological evaluation from the USEPA indicated that “93% of threatened and endangered species as well as 96% of their habitats could likely be harmed by glyphosate.” (Erickson, B., Nov. 30,2020, Chemical & Engineering News). As is customary, a 60 day period was allowed for public comments on this draft Agency report. EPA’s final biological evaluation on glyphosate’s potential danger to listed species is expected to be released following an internal Agency review. “If the final evaluation finds that glyphosate is likely to adversely impact any endangered species, the EPA would then [be required to] consult with the Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service to determine the extent of the impact and to develop a plan to protect the affected species.” (Erickson, B., Nov. 30, 2020, Chemical & Engineering News)

Rachel Carson and the Current Endangered Species Act

Although Carson did not live to see creation of the current, (1973) Endangered Species Act (ESA), her work raised environmental concerns that helped to bring it about. Further, Carson wrote in Silent Spring,

“To destroy the homes and food of wildlife is perhaps worse in the long run than direct killing.” (p. 74, Silent Spring, 1962).

This statement’s significance foreshadows the 1973 ESA provision that requires regulators to protect individual members of a listed species from directly hazardous pesticide products, as well as to protect the food sources and the habitat of individual members of a listed species from hazardous pesticide products. This is more protection than that which is required under FIFRA (the current regulation controlling pesticides’ review and registration for nonlisted species by the USEPA). In other words, nontarget species not covered by the ESA have no specific requirement to be protected as individuals, or to have their food sources and their habitats protected from dangerous pesticides. The vulnerability of non-listed wildlife to pesticides’ hazards was expressed in stark terms by Dr. Charles Benbrook who when giving the Rachel Carson Memorial lecture stated:

“In the real world of pesticide regulation birds, fish and bees are expendable.” (Benbrook, C.,“Prevention, not profit, should drive pest management,” Pesticides News, 82,December, 2008, 12-17)

Under the current (1973) ESA, listed species are considered indispensable. In contrast individuals in those species not covered by ESA are considered “expendable.” In view of the planet-wide stressful conditions facing wildlife as predicted by scientists, and the expectation that thousands of species will become extinct, can we afford to deem any of our wildlife allies as expendable?

If beneficial life forms are to thrive under climate change and other potential hazards, their food sources and habitats should be as well protected from pesticides’ dangers as those of any listed species.

Creation of Our Current 1973 ESA

The late Conservationist, Scientist, and Professor Dr. Lee Merriam Talbot (1930-2021) wrote and helped to enact the current (1973) Endangered Species Act (ESA).

The 1973 ESA: What it is/What it does

“The original 1973 ESA had strong language and the clout to enforce the words. It stated that no government agency could perform any activity that would lead to the extinction of an organism on the list and that all government agencies must cooperate to prevent extinction…” (Dashefsky, S., Environmental Literacy, p. 79-80)

The 1973 ESA has the authority to restrain actions on both public and private land that might threaten the survival and habitat of threatened and endangered plant and animal species. (Rockwood, Stewart, & Dietz, Foundations of Environmental Sustainability, 2008, p. 142)

ESA is intended to provide a means whereby the ecosystems upon which endangered species and threatened species depend may be conserved. (Rockwood, Stewart, & Dietz, Foundations of Environmental Sustainability, 2008, p. 171)

ESA Under Attack

“Since its inception, the 1973 Endangered Species Act has been underfunded and gradually watered down.” (Dashefsky, S., Environmental Literacy, p. 79-80) (Footnote 3)

During early days of the Trump administration the ESA was confronted by a pro-fossil fuel and pro-development administration in the White House.

Lee Talbot Challenged ESA Detractors

Responding to attacks on the ESA, Professor Lee Talbot of George Mason University reported in his December 29, 2017 Washington Post article that “The Endangered Species Act has saved 99% of all animals under its protection from extinction… 85% of the North American birds listed under the ESA have either increased in numbers or remained stable since being protected.” (Talbot, L., “Remember when the GOP supported conservation?” Washington Post, 12-29-17)

He showed that “our [environmental] laws have preserved critical natural resources…” He further declared, “…we should hold politicians who would undermine environmental protections accountable, because as Americans, we value our wildlife and wild places over short-term profits, and we want them preserved for future generations.” (Talbot, L., “Remember when the GOP supported conservation?” Washington Post, 12-29-17)

About the ESA and Pesticides

Under the 1973 ESA, our US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) is required to regulate chemical pesticides in such a way that individuals belonging to endangered or threatened species are protected from the hazards of pesticide products. When applied at the level registered as “protective” for non-listed, nontarget populations pesticides registered with USEPA can be considered dangerous to listed species. Why? The standard for assessing the toxic risk of a pesticide product to wildlife is “no unreasonable risk to the environment.” This can represent a subjective determination. For listed plant and animal species under ESA the pesticide standards are more protective than those covering non-listed species. Without the ESA, regulators would not be required to establish conditions that protect individual members of a listed species or their food and habitat from pesticides’ adverse impacts.

Expressed another way, levels of concern for the listed species include direct as well as indirect hazards of pesticides. Direct hazards to individuals in the listed species, include killing. Indirect hazards refer to loss of food sources and/or loss of sources that provide habitat or shelter from predators.

ESA’s Pesticide Policy Explained in Regulatory-type Language:

“Ecological risk assessments are conducted on virtually all outdoor use pesticides prior to registration. The same risk assessments apply to listed species as for other nontarget species. But the levels of concern [the pesticide exposures considered hazardous for listed species] are more conservative [protective] than for other nontarget species in accordance with their precarious status.” (Larry Turner, USEPA, Presentation 9-26-1998)

For example: Plants have pollinators. Animals require food. Listed species assessments take such factors into account, “although in general it is sufficient to protect populations, rather than individuals, of pollinators or food organisms.” (Larry Turner, USEPA, Presentation 9-26-1998)

For listed species, with respect to a pesticide’s toxic effects protecting the species means protecting at the level of individuals. In the case for non-listed species, protection is intended to be at the population, not the individual, level. Further, non-listed species are not protected from pesticide-related loss of habitat or of food sources.

About Chlorantraniliprole

An example of the enhanced protection for listed species from a pesticide’s hazards under ESA is illustrated by a chart from the (2008) EPA Fact Sheet for chlorantraniliprole (an anthranilic diamide chemical insecticide with the CAS # of 500008-45-7 and with a mode of action described as interruption of normal muscle contraction). This insecticide is considered by USEPA to represent a very low hazard to non-target/non-listed species. Yet, both the EPA Fact sheet and the label for the chlorantraniliprole-containing insecticide product, trade name Acelepryn (registered for “systemic control of listed pests on turf, landscape ornamentals, sod farms & interior plantscapes”) include the following “Aquatic Environmental Hazard” information: “This pesticide is toxic to aquatic invertebrates, oysters and shrimp. Do not apply directly to water. Drift and runoff may be hazardous to aquatic organisms in water adjacent to use sites.” Information for chlorantraniliprole relevant to the Endangered Species Act (ESA) is found in the 2008 USEPA Fact Sheet for this chemical insecticide. It shows that chlorantraniliprole can present either a direct (D) and/or indirect (I) level of concern as indicated by a “yes” to virtually all groups of listed (endangered/threatened species) covered (with the exception of vascular underwater plants): Below is the chart excerpted from the 2008 EPA Fact Sheet for chlorantraniliprole (Table 21):

An example of the enhanced protection for listed species from a pesticide’s hazards under ESA is illustrated by a chart from the (2008) EPA Fact Sheet for chlorantraniliprole (an anthranilic diamide chemical insecticide with the CAS # of 500008-45-7 and with a mode of action described as interruption of normal muscle contraction). This insecticide is considered by USEPA to represent a very low hazard to non-target/non-listed species. Yet, both the EPA Fact sheet and the label for the chlorantraniliprole-containing insecticide product, trade name Acelepryn (registered for “systemic control of listed pests on turf, landscape ornamentals, sod farms & interior plantscapes”) include the following “Aquatic Environmental Hazard” information: “This pesticide is toxic to aquatic invertebrates, oysters and shrimp. Do not apply directly to water. Drift and runoff may be hazardous to aquatic organisms in water adjacent to use sites.” Information for chlorantraniliprole relevant to the Endangered Species Act (ESA) is found in the 2008 USEPA Fact Sheet for this chemical insecticide. It shows that chlorantraniliprole can present either a direct (D) and/or indirect (I) level of concern as indicated by a “yes” to virtually all groups of listed (endangered/threatened species) covered (with the exception of vascular underwater plants): Below is the chart excerpted from the 2008 EPA Fact Sheet for chlorantraniliprole (Table 21):

-

- Terrestrial and semi-aquatic plants monocots & dicots: Yes (D & I)- This indicates a level of concern for both direct (D) and indirect (I) effects of chlorantraniliprole on this group of listed plant species

- Terrestrial Invertebrates: Yes (D), No (I)

- Birds: No (D), Yes (I)

- Terrestrial & Aquatic phase amphibians: No (D), Yes (I)

- Reptiles: No (D), Yes (I)

- Mammals: No (D), Yes (I)

- Aquatic Vascular Plants: No (D), No (I)

- Freshwater Fish: No (D), Yes (I)

- Freshwater Crustaceans: Yes (D), Yes (I)

- Molluscs: Yes (D), Yes (I)

- Marine/Estuarine Fish: No (D), Yes (I)

- Marine/Estuarine Invertebrates: Ye s(D), No (I)

Out of the 12 groups representing listed species there are “yes” levels of concern for direct chlorantraniliprole effects in 5 groups. In contrast, out of the 12 groups representing listed species there are “yes” levels of concern for indirect chlorantraniliprole effects (food, habitat, etc) in 9 groups, this is nearly double the number showing direct effects. Thus, even groups of listed species that lack a level of concern for direct adverse pesticide effects can be harmed by certain indirect hazardous effects of pesticides at the level of use registered by the USEPA. This can be significant in terms of a species ability to survive.

ESA and Protection of Human Health

There can be a human health benefit of the ESA where pesticides’ application levels are reduced to protect endangered or threatened species, then the direct exposures to hazardous chemical pesticides are lowered for: farm workers, residents of agricultural areas where pesticides are applied, children consuming pesticide contaminated food, and residents of suburban areas where neighbors apply pesticides. Why? Pesticides’ application rates are required to be reduced due to levels of concern for listed species as directed by local or federal compliance with the ESA. Failure to comply with the ESA may lead to fines and other charges.

There can be a human health benefit of the ESA where pesticides’ application levels are reduced to protect endangered or threatened species, then the direct exposures to hazardous chemical pesticides are lowered for: farm workers, residents of agricultural areas where pesticides are applied, children consuming pesticide contaminated food, and residents of suburban areas where neighbors apply pesticides. Why? Pesticides’ application rates are required to be reduced due to levels of concern for listed species as directed by local or federal compliance with the ESA. Failure to comply with the ESA may lead to fines and other charges.

Furthermore, when listed species are protected from indirect pesticide hazards, there can be indirect benefits to people due to the natural ecosystem services provided by such species. For example mollusks can help clean the water in estuaries, lakes and rivers by removing debris. This is an important service but it may not be protected as fully by regulators unless the mollusks are from a listed species (as in the example from chlorantraniliprole).

Conclusions

Rachel Carson’s statement “To destroy the homes and food of wildlife is perhaps worse in the long run than direct killing.” (p. 74, Silent Spring, 1962). calls attention to the failure of the current regulations under FIFRA to ensure that non-listed species are saved from chemical pesticides’ indirect adverse effects since there are no requirements to protect their food sources or habitats from pesticide hazards. Carson’s statement is reinforced by the analysis from EPA scientists who determined that for the pesticides glyphosate and chlorantraniliprole the indirect adverse effects on listed species’ habitats and food sources appeared more hazardous than were the chemicals’ direct adverse effects on listed individuals.

The ESA has an impressive record despite attempts by industry forces to render it ineffective.

The inadequacy of protection for non-listed species under the current pesticide regulations (FIFRA) employed at the USEPA to register pesticide products is supported by Dr. Benbrook’s statement “In the real world of pesticide regulation birds, fish and bees are expendable.” (Benbrook, C.,“Prevention, not profit, should drive pest management,” Pesticides News, 82,December, 2008, 12-17)

Lack of Protection from Pesticides for Soil-Dwelling Organisms

Soil dwelling organisms including non-listed species are increasingly stressed by climate change. A recent report states that the USEPA does not have sufficient testing requirements or tools in place to quantify the risks to this group from pesticides. Why? “Pesticides of all types pose a clear hazard to soil invertebrates… [S]oil organisms [need] to be represented in any risk analysis of a pesticide that has the potential to contaminate soil [so that] any significant risk [can] be mitigated in a way that will specifically reduce harm to the soil organisms that sustain important ecosystem services.” (Gunstone, T., et al, “Pesticides and Soil Invertebrates: A Hazard Assessment,” Frontiers in Environmental Science, May 2021, v. 9, Article 643847)

Now Called-For: An Abundant Species Act

Environmental advocates Carl Safina and Paul Greenberg recently proposed creation of a new Abundant Species Act. They reason that: “As pressures on wildlife rise, we need to protect populations before they decline. We need an Abundant Species Act whose goal is assuring that wildlife on the land and in the waters and skies are as visible as roads, rails or wind turbines.” (Greenberg, P., and Carl Safina, “We Don’t Need More Concrete and Steel,” The New York Times, 4-15-21)

We at RCLA support this call from Safina and Greenberg. We urge, further, that incorporated into any Abundant Species Act there would be protection of food sources and habitats found in the 1973 ESA.

People Protecting Species from Pesticides and Other Hazards

Environmental advocates tell us that people want to know what they can do to protect wildlife during these troubling times. Here are suggestions for what you can do to help:

Speak out and defend the current 1973 ESA from detractors

Show appreciation to those who support strengthening the 1973 ESA

Contribute to environmental organizations with a strong supportive policy for the current 1973 ESA

Research any listed species in your community and find out whether the ESA pesticide regulations are being enforced for their protection and if not, why not

Advocate for inclusion of more species, such as the Monarch Butterfly in the listed category under the 1973 ESA

Support the current legislation “Recovering America’s Wildlife Act of 2021 (S.2372).” It has provisions for funding to states and tribes to recover wildlife species at risk, those not yet listed and other species in need of conservation. Ask your legislators to back this legislation.

Propose legislation to educate farmers, gardeners and others about the toxic hazards of pesticides to individual plants and animals, their food sources and habitats whether they are listed or non-listed species. Support efforts to inform pesticide users of pesticides’ hazards to human health. The recent linking of cancer with glyphosate should indicate the need for caution where chemical pesticides are concerned.

Support efforts that focus on education of young people and students about the essential services of our wildlife allies.

Support efforts to create new legislation incorporating the ESA scope of protection (requirement for reducing direct and indirect hazards by chemical pesticides to our wildlife allies) so that wildlife populations can thrive and help to sustain our societies.

Remind legislators of Dr. Charles Benbrook’s statement: “In the real world of pesticide regulation birds, fish and bees are expendable.”

Also, remind them of Rachel Carson’s warning: “To destroy the homes and food of wildlife is perhaps worse in the long run than direct killing.” (p. 74, Silent Spring, 1962).

Ask legislators if they can justify not providing our wildlife allies with the best support we can give by bringing them all under the protection of a shield law incorporating elements of the 1973 Endangered Species Act. As the environmental advocates Safina and Greenberg have stated, “We need an Abundant Species Act.” This needs to be seriously considered at our nation’s highest level.

Finally, Please Donate to:

RCLA

11701 Berwick Road

Silver Spring MD 20904

Diana Post, President, RCLA 9-7-21

Footnotes

- In 2018 a groundskeeper from California sued Monsanto claiming exposure to glyphosate-containing, Roundup caused his non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. “The jury ruled in his favor. It was the first of many trials against Monsanto for failing to inform the public about the carcinogens in Roundup, and costing the company more than $11 billion in settlements.” (Meade, M., in Green American, Summer 2021). Note: The USEPA has stated that “glyphosate is not likely to be carcinogenic to humans.” (Bloch, S., The Counter)

- After Bayer shares dropped 5%, on the day following the Judge’s announcement, the company reportedly “called into question the future sale of glyphosate-based products to gardeners in the United States.”

- In 1978 an Endangered Species Review Committee was established that could override the Act if the economic advantages outweighed the ecological effects. Later a special panel, unofficially called the “God Squad,” had the power to overrule the placement of any animal on the endangered species’ list, if listing would pose a burden to business interests. It could even remove species already on the list. ” (Dashefsky, S., Environmental Literacy, p. 79-80)